EVIDENCE BASED PRACTICES

TIER 1: UNIVERSAL

general tips & Basic strategies

Allow for Movement

Allow students to use fidget toys, doodle, or knit. Students can still pay attention and may be able to focus better when their bodies are moving.

Allow students to work and sit in various parts of the classroom

For some students, working standing up, sitting cross-legged on the floor, or lying on the floor maybe more conducive to learning than sitting feet flat on the floor at a desk. Teach students the expected behavior first (model it, have them practice multiple times) and be clear about expectations for work completion.

Avoid Power Struggles

Power struggles often occur after the request of a teacher. Make your redirection statement/statement of expectation (which students will already know because of your explanation, modeling, and teaching of classroom rules and consequences). “You know what is expected. Take your time to compose yourself and then take care of X so you can rejoin our learning.” Avoid eye contact, look away, and walk away. Give the student a moment to regain composure.

Move Around The Classroom

- Strong teachers are constantly adjusting their proximity to students during a lesson. Staying active and moving around the room is a great classroom management tool as it keeps students accountable to the classroom expectations.

- If you anticipate off-task behavior, physically moving yourself closer to the students who may struggle can help avoid difficult behavior.

- If a behavior begins to escalate, seating yourself (or a classroom support person), near students who are struggling can often be enough to get them back on task.

- Request extra staff support or volunteers (adults, older peer mentors) for the classroom to sit within close proximity of a student to improve behavior.

Token Economy

A token economy rewards good behavior with tokens that can be exchanged for something desired. A token can be a chip, coin, star, sticker, or something that can be exchanged for what the student wants to buy.

Token economy systems are one of the most effective ways to reduce behavior problems and to motivate kids to follow the rules. When a token is given, it is important to pair it with verbal praise. Verbal feedback should be timely, positive, and specific to the positive behavior.

Token economies work well when there are a variety of reinforcers to reward positive behavior. What will motivate students? To compile a list of rewards, a teacher will want to consider the interests of the class and perhaps even ask the class to brainstorm ideas.

Contingency contracts can be developed for a single student or a group of students. A contingency contract is an agreement between a student or group of students and teacher, which outlines a specific behavioral expectation. The contract includes a menu of reinforcers. When the student meets the expectation, they receive a reward/reinforcer.

Students should have an understanding of what a contract is. All the students involved be a part of the development of the contract: identifying the goal, setting the time frame, updating the contract when needed, and signing the contract to make it official

If the goal of the group contingency is positive peer interactions, then the group receives a reinforcer when individual students make a positive comment; in this way, students are supporting each other to behave appropriately. As an example, every time a student makes a positive comment to another student, the teacher puts a check mark on a chart. When 20 positive remarks have been made by the group, 20 minutes of free time is earned.

For more information on developing Contingency Contracts visit these websites:

Intervention Central: Behavior Contracts and The University of Kansas: Positive Reinforcement

A token economy rewards good behavior with tokens that can be exchanged for something desired. A token can be a chip, coin, star, sticker, or something that can be exchanged for what the student wants to buy.

Token economy systems are one of the most effective ways to reduce behavior problems and to motivate kids to follow the rules. When a token is given, it is important to pair it with verbal praise. Verbal feedback should be timely, positive, and specific to the positive behavior.

Token economies work well when there are a variety of reinforcers to reward positive behavior. What will motivate students? To compile a list of rewards, a teacher will want to consider the interests of the class and perhaps even ask the class to brainstorm ideas.

- Do they need rewards that are more motivating?

- Do they need to be rewarded on a more consistent/frequent schedule?

- Students who do not respond well to the classroom token economy system may need a different reinforcer or may need to be recognized and encouraged more often. What is reinforcing to one group of students may not be reinforcing to another.

Contingency contracts can be developed for a single student or a group of students. A contingency contract is an agreement between a student or group of students and teacher, which outlines a specific behavioral expectation. The contract includes a menu of reinforcers. When the student meets the expectation, they receive a reward/reinforcer.

Students should have an understanding of what a contract is. All the students involved be a part of the development of the contract: identifying the goal, setting the time frame, updating the contract when needed, and signing the contract to make it official

If the goal of the group contingency is positive peer interactions, then the group receives a reinforcer when individual students make a positive comment; in this way, students are supporting each other to behave appropriately. As an example, every time a student makes a positive comment to another student, the teacher puts a check mark on a chart. When 20 positive remarks have been made by the group, 20 minutes of free time is earned.

For more information on developing Contingency Contracts visit these websites:

Intervention Central: Behavior Contracts and The University of Kansas: Positive Reinforcement

Resources References

Carr, J. E., Fraizer, T. J., & Roland, J. P. (2005). Token economy. Encyclopedia of behavior modification and cognitive behavior therapy, 2, 1075-1079.

Kerr, M.M., and Nelson, C.M. (2012). Strategies for Addressing Behavior Problems in the Classroom. Pearson Education Inc., New Jersey

Carr, J. E., Fraizer, T. J., & Roland, J. P. (2005). Token economy. Encyclopedia of behavior modification and cognitive behavior therapy, 2, 1075-1079.

Kerr, M.M., and Nelson, C.M. (2012). Strategies for Addressing Behavior Problems in the Classroom. Pearson Education Inc., New Jersey

implement clear expectations

Working with your students develop a sustainable school and classroom culture that is conducive for learning and fosters a climate of acceptance, respect, and high expectations.

1. Develop clear behavioral expectations

What behaviors will represent and support those rules school-wide? In the classroom? On the playground? In after-school extra-curricular activities?

Create a Rules-Within-Routines Matrix. This matrix will specifically outline what each expectation looks like across environments.

Whether your school is developing school-wide behavioral expectations or you are developing behavioral expectations for your class, the process is the same:

Resources

2. Model the Desired Behavior

Modeling includes a demonstration of the desired behavior (by teacher or peer) and shows step-by-step what is expected for a specific learning activity, task, or social skill.

1. Develop clear behavioral expectations

What behaviors will represent and support those rules school-wide? In the classroom? On the playground? In after-school extra-curricular activities?

Create a Rules-Within-Routines Matrix. This matrix will specifically outline what each expectation looks like across environments.

Whether your school is developing school-wide behavioral expectations or you are developing behavioral expectations for your class, the process is the same:

- Engage the students so they are participating in the development of the expectations.

- Ask: “How do we want our school/classroom to function so that we can all learn, feel safe, and feel accepted?”

- This is much more effective than having the rules come as a directive from the principal or teacher.

- Begin the year by teaching, modeling, and practicing those behaviors. Students will need continued modeling and practice throughout the year, especially after school breaks and holidays. Conduct practice as just that, practice – not punishment.

- Add to, edit, and revise your Rules-Within Routine Matrix throughout the year to ensure it reflects the challenges faced in different environments, including field trips or special events.

Resources

- Classroom Schedules/Routines (Pinterest)

- Rules Within Routines Matrix (PDF)

- Rules Within Routines Matrix (DOCX)

2. Model the Desired Behavior

Modeling includes a demonstration of the desired behavior (by teacher or peer) and shows step-by-step what is expected for a specific learning activity, task, or social skill.

Modeling is most effective when the model is somehow connected to the student. For example they look up to their peer, the student is the same gender, or is in the same social group.

Video modeling is a well-researched strategy. The student watches a video of the skill or behavior they are working on and imitates that behavior. The visual models enhance student understanding and are highly motivating. Video Modeling has been shown to be especially effective when working with children with autism on skills such as daily living, communication, social skills, academics, and reducing aggressive behavior. The use of videos is also more likely to help generalize the skill to different environments, as well as maintain that skill in the future.

For more information on video modeling:

3. Post a schedule

Posting a schedule allows students to know the expectations for the day, helps to develop their time management skills, and alerts students to potential irregularities in the day.

For more information on developing schedules and routines:

Video modeling is a well-researched strategy. The student watches a video of the skill or behavior they are working on and imitates that behavior. The visual models enhance student understanding and are highly motivating. Video Modeling has been shown to be especially effective when working with children with autism on skills such as daily living, communication, social skills, academics, and reducing aggressive behavior. The use of videos is also more likely to help generalize the skill to different environments, as well as maintain that skill in the future.

For more information on video modeling:

3. Post a schedule

Posting a schedule allows students to know the expectations for the day, helps to develop their time management skills, and alerts students to potential irregularities in the day.

For more information on developing schedules and routines:

References

Banda, D.R., Matuszny, R.M., & Turkan, S. (2007). Video modeling strategies to enhance appropriate behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders.

Teaching Exceptional Children 39(6), 47-52. doi: 10.1177/004005990703900607

Chandler, L. & Dahlquist, C. (2010). Functional assessment: Strategies to prevent and remediate challenging behaviors in school settings. London:

Pearson.

Denton, P. & Kriete, R. (2000). The first six weeks of school. Turner Falls, MA: Northeast Foundation for Children.

Kerr, M. & Nelson, C.M. (2010). Strategies for addressing behavior problems in the classroom (6th Ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill

Prentice-Hall.

Banda, D.R., Matuszny, R.M., & Turkan, S. (2007). Video modeling strategies to enhance appropriate behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders.

Teaching Exceptional Children 39(6), 47-52. doi: 10.1177/004005990703900607

Chandler, L. & Dahlquist, C. (2010). Functional assessment: Strategies to prevent and remediate challenging behaviors in school settings. London:

Pearson.

Denton, P. & Kriete, R. (2000). The first six weeks of school. Turner Falls, MA: Northeast Foundation for Children.

Kerr, M. & Nelson, C.M. (2010). Strategies for addressing behavior problems in the classroom (6th Ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill

Prentice-Hall.

engage students

Meaningful Instruction & Activities

By providing meaningful instruction and learning activities, student learn to use their critical and creative thinking skills.

By providing meaningful instruction and learning activities, student learn to use their critical and creative thinking skills.

- Differentiate how students receive content, how they engage in the learning process, and how they demonstrate their learning via a product, following the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

- Integrate technology. For more ideas on engaging students and enlivening your lessons, visit these sites:

- Best Technological Ways to Increase Engagement in Classroom

- 5 Reasons Technology in the Classroom Engages Students

- Integrating Technology in the Classroom: It Takes More than Computers

- Kahoot it!

- Plicker Application

- PollEv Presenter

- How to Integrate Technology

- Vary learning experiences: Small group work gives students more opportunities to engage and get involved in their learning, which increases their on-task behavior. Students exhibit more disruptive behaviors during whole-class, teacher-led activities.

- Avoid worksheets, busy work, and downtime. Always provide students with more work to engage with, more learning to achieve, so they do not become bored and feel the need to entertain themselves--or others! Students can always be reading a book, working on a project, or writing for an assignment.

Choice

Using choice can motivate students and is a powerful tool for differentiating instruction.

Choice allows students more control of what they are learning and how they are learning. In addition, choice increases student engagement and motivation. It results in a classroom that is focused on the co-construction of knowledge, instead of relying on the teacher as the source of all knowledge. When working with a student who is resistant to work completion, giving them choice can have a positive impact on the on-task behavior.

Using choice can motivate students and is a powerful tool for differentiating instruction.

Choice allows students more control of what they are learning and how they are learning. In addition, choice increases student engagement and motivation. It results in a classroom that is focused on the co-construction of knowledge, instead of relying on the teacher as the source of all knowledge. When working with a student who is resistant to work completion, giving them choice can have a positive impact on the on-task behavior.

- Make sure the choices are feasible and fit the activity/assignment.

- Choices should be clear.

- Choices should be limited to 2 or 3.

- Be clear about the expectations:

- Keep students accountable and on task by having them identify what they are working on. This could be as simple as a post-it with the tasks written in order in which they are to be completed.

- Teach time management and task organization. This will help students learn to make decisions.

Group Response

When students respond to group academic content, they are actively engaged and more likely to learn material being taught.

Response Cards

Students can respond as a group by displaying 'response cards' which display their answers to a teacher question or academic problem.

These activities can transform the learning in your class. In addition, response cards can be used as an assessment, to see what learning has occurred and what instruction still needs to occur, and with whom.

By using response cards:

Learning is a social act. When teachers and students can create knowledge together a more productive learning environment is created. Think about ways you can include student voice and student choice in your curriculum.

Students can respond to prompts or questions using student response cards:

Response cards help engage all students as the entire class is responding to each question, instead of just one child per question.

For more information and ideas on response cards:

Here are 3 more activities to engage all students

When students respond to group academic content, they are actively engaged and more likely to learn material being taught.

Response Cards

Students can respond as a group by displaying 'response cards' which display their answers to a teacher question or academic problem.

These activities can transform the learning in your class. In addition, response cards can be used as an assessment, to see what learning has occurred and what instruction still needs to occur, and with whom.

By using response cards:

- Every student practices the skill every time

- Students aren’t waiting for their turn (and tuning out)

- It is easy to look around and see who gets the answer right

- Students can’t just repeat the student who answers first

Learning is a social act. When teachers and students can create knowledge together a more productive learning environment is created. Think about ways you can include student voice and student choice in your curriculum.

Students can respond to prompts or questions using student response cards:

- Labeled with answer choices: true/false or A, B, C, D

- Color coded, such as green for “yes” and red for “no”

- Pictures of possible responses

Response cards help engage all students as the entire class is responding to each question, instead of just one child per question.

For more information and ideas on response cards:

- Student Response Cards

- Printable Response Cards:

- Make and Take

- Response Cards: Increasing Student Engagement

Here are 3 more activities to engage all students

- Turn & Talk provides students with a partner with whom to share their comments and questions.

- Gauge understanding by asking students to show a thumbs up if they fully understand, or a thumb to the side if they are still unclear. This also provides students some anonymity and autonomy with their response.

- With individual white boards, students respond on their board and then display it for the teacher.

References

Armstrong, T. (2000). Multiple intelligences in the classroom. (2nd Ed.) Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Bender, W. N. (2012). Differentiating instruction for students with learning disabilities: New best practices for general and special educators (3rd Ed.).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Boushey, G. & Moser, J. (2014). The daily five: Fostering independence in the elementary grades (2nd Ed.) Stenhouse.

Gregory, G.H. & Chapman, C. (2006). Differentiated instructional strategies: One size doesn’t fit all. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Hall, T. E., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. H. (Eds.). (2012). Universal design for learning in the classroom: Practical applications. New York: Guilford Press.

Hallermann, S., Larmer, J., & Mergendoller, J. R. (2011). PBL in the elementary grades: step-by-step guidance, tools and tips for standards-focused k-5

projects. Novato, CA: Buck Institute for Education.

Kaplan, P., Rogers, V., & Webster, R. (2008). Differentiated instruction made easy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Larmer, J., Ross, D., & Mergendoller, J. R. (2009). PBL starter kit: To-the-point advice, tools and tips for your first project in middle or high school. Novato,

CA: Buck Institute for Education.

Riley, J. L., McKevitt, B., C., Shriver, M. D., & Allen, K. D. (2011). Increasing on-task behavior using teacher attention delivered on a fixed-time schedule.

Journal of Behavioral Education, 20, 149-162. DOI: 10.1007/s10864-011-9132-y.

Simonsen, B., Little, C. A., & Fairbanks, S. (2010). Effects of task difficulty and teacher attention on the off-task behavior of high-ability students with

behavior issues. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 32(2), 245-260.

Armstrong, T. (2000). Multiple intelligences in the classroom. (2nd Ed.) Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Bender, W. N. (2012). Differentiating instruction for students with learning disabilities: New best practices for general and special educators (3rd Ed.).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Boushey, G. & Moser, J. (2014). The daily five: Fostering independence in the elementary grades (2nd Ed.) Stenhouse.

Gregory, G.H. & Chapman, C. (2006). Differentiated instructional strategies: One size doesn’t fit all. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Hall, T. E., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. H. (Eds.). (2012). Universal design for learning in the classroom: Practical applications. New York: Guilford Press.

Hallermann, S., Larmer, J., & Mergendoller, J. R. (2011). PBL in the elementary grades: step-by-step guidance, tools and tips for standards-focused k-5

projects. Novato, CA: Buck Institute for Education.

Kaplan, P., Rogers, V., & Webster, R. (2008). Differentiated instruction made easy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Larmer, J., Ross, D., & Mergendoller, J. R. (2009). PBL starter kit: To-the-point advice, tools and tips for your first project in middle or high school. Novato,

CA: Buck Institute for Education.

Riley, J. L., McKevitt, B., C., Shriver, M. D., & Allen, K. D. (2011). Increasing on-task behavior using teacher attention delivered on a fixed-time schedule.

Journal of Behavioral Education, 20, 149-162. DOI: 10.1007/s10864-011-9132-y.

Simonsen, B., Little, C. A., & Fairbanks, S. (2010). Effects of task difficulty and teacher attention on the off-task behavior of high-ability students with

behavior issues. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 32(2), 245-260.

TIER 2: TARGETED

off task behaviors

Off-Task Behaviors are defined as physical, verbal, or passive behaviors that result in students not attending to or engaging in teacher instruction, class activities, or assignments.

Here are some common off-task behaviors:

Physical and verbal off-task behaviors interfere with teacher instruction and the learning of all students within the classroom, not just the achievement of the off-task student.

In addition, behavior problems negatively affect teachers and students: Behavior problems in the classroom are often cited as a main reason teachers leave the profession, and misbehavior has been identified as a predictor of student dropout.

Physical off-task behaviors include fidgety behaviors, moving around the classroom, and creating noise with objects.

Verbal off-task behaviors include speaking out of turn, calling out, and yelling. These overt behaviors are problematic because they directly interfere with the teacher’s ability to deliver instruction and potentially disrupt the learning of all students in the class.

Passive off-task behaviors may include a general inattentiveness, such as putting one’s head on the table, falling asleep, and delaying the start of an assignment or not completing class assignments and tasks. Passive behaviors interfere directly with that student’s learning; however, because these behaviors do not interfere with the learning of other students, this behavior may go unnoticed by teachers or even be purposefully ignored so instruction may continue.

- fidgety behaviors

- creating noise with objects

- speaking out of turn

- falling asleep

- not completing tasks

Physical and verbal off-task behaviors interfere with teacher instruction and the learning of all students within the classroom, not just the achievement of the off-task student.

In addition, behavior problems negatively affect teachers and students: Behavior problems in the classroom are often cited as a main reason teachers leave the profession, and misbehavior has been identified as a predictor of student dropout.

Physical off-task behaviors include fidgety behaviors, moving around the classroom, and creating noise with objects.

Verbal off-task behaviors include speaking out of turn, calling out, and yelling. These overt behaviors are problematic because they directly interfere with the teacher’s ability to deliver instruction and potentially disrupt the learning of all students in the class.

Passive off-task behaviors may include a general inattentiveness, such as putting one’s head on the table, falling asleep, and delaying the start of an assignment or not completing class assignments and tasks. Passive behaviors interfere directly with that student’s learning; however, because these behaviors do not interfere with the learning of other students, this behavior may go unnoticed by teachers or even be purposefully ignored so instruction may continue.

Tier 2 Research Based Strategies

Here are some Tier 2 research based strategies that can be used with a class or an individual to increase appropriate behaviors:

Teams receive points by displaying the appropriate behavior and receive a “foul” if an individual within the team displays the identified inappropriate behavior.

The Good Behavior Game

Requires that a class be divided into teams, who work towards displaying appropriate behaviors and thereby earning points. Teams receive points by displaying the appropriate behavior and receive a “foul” if an individual within the team displays the identified inappropriate behavior. The winning team is rewarded at the end of class and also earns a token towards a larger class reward.

How to:

Materials:

Here are some Tier 2 research based strategies that can be used with a class or an individual to increase appropriate behaviors:

Teams receive points by displaying the appropriate behavior and receive a “foul” if an individual within the team displays the identified inappropriate behavior.

The Good Behavior Game

Requires that a class be divided into teams, who work towards displaying appropriate behaviors and thereby earning points. Teams receive points by displaying the appropriate behavior and receive a “foul” if an individual within the team displays the identified inappropriate behavior. The winning team is rewarded at the end of class and also earns a token towards a larger class reward.

How to:

Materials:

- Team Earnings chart (or tally on whiteboard)

- Reward menu (ex. Extra recess, 5 min. for a class game, snacks, gum, extra reading time)

- Reward items

- Class reward tokens and token container

- As a class, identify desired behaviors (within varied learning situations: whole group, small group, peer work, or individual work). Model, demonstrate, and role play to ensure student understanding. Use of Rules within Routines Matrix may be effective and may help with generalization to other classes and settings.

- Explain that students will have the opportunity to earn rewards for appropriate behavior.

- As a class, identify desired rewards (ex: special activities, snacks). Designate the point value/cost for the various items. Create goals based on points per day (for example, 10 points available per day). Pre-determine when students can use their banked points to exchange for a reward item. For example, depending on the age and ability of students, and in order to build their endurance for demonstrating the appropriate behaviors, you may want to offer the reward exchange opportunity in smaller increments, and gradually extend this time (end of a class period, middle of the day, end of the day, end of the week.)

- As a class, identify behaviors to avoid, particularly in areas where students have struggled (i.e. negative language, not cooperating during group work).

- Post the rules of the game.

- Divide the class into equal teams (3-4, depending on class size), and have teams sit together. Review established target behaviors before each installment of the game.

- Say “Game on!”

- Award points appropriately and consistently. The behavioral expectations among students may vary; improvements in behavior should be noted and awarded on an individual basis.

- Call “foul” when inappropriate behaviors are demonstrated, and record the foul for that team.

- At the end of the class (or other designated time), the winning team will have earned the most points for the identified appropriate behaviors, as well as receiving a minimal number of fouls, without going over a designated number of fouls (3-5). Do not identify this number, so students are motivated to continue behaving appropriately. For example, if one team was receiving many fouls, other teams may choose to behave inappropriately, but not more than the other team, in order to earn the reward.

- The winning team receives a reward, as well as a token towards a larger class reward.

Reference:

Flower, A., McKenna, J., Muething, C. S., Bryant, D. P., & Bryant, B. R. (2013). Effects of the Good Behavior Game on classwide off-task behavior in a high

school basic algebra resource classroom. Behavior Modification 38(1), 45-68. doi: 10.1177/0145445513507574

Resources:

Get 'Em On Task (Tier II, Elementary)

When the sound goes off, the teacher identifies students by name who are off-task, and instructs them to mark an X on their individual score cards. A chart is created to identify and track daily behaviors. If appropriate behaviors are demonstrated, the corresponding space on the chart is selected, which may show a Mystery Motivator symbol, whereby a prize is selected from a menu of options.

Get ‘Em on Task requires a computer or application to provide a random auditory signal in the classroom to alert teachers and students to monitor behaviors and participation. When the sound goes off, the teacher identifies students by name who are off-task, and instructs them to mark an X on their individual score cards; students who are on-task are praised and told to give themselves a point. At the end of a designated time period, students use the points for a reward, pre-determined by the students and teacher.

How to:

Materials:

Flower, A., McKenna, J., Muething, C. S., Bryant, D. P., & Bryant, B. R. (2013). Effects of the Good Behavior Game on classwide off-task behavior in a high

school basic algebra resource classroom. Behavior Modification 38(1), 45-68. doi: 10.1177/0145445513507574

Resources:

Get 'Em On Task (Tier II, Elementary)

When the sound goes off, the teacher identifies students by name who are off-task, and instructs them to mark an X on their individual score cards. A chart is created to identify and track daily behaviors. If appropriate behaviors are demonstrated, the corresponding space on the chart is selected, which may show a Mystery Motivator symbol, whereby a prize is selected from a menu of options.

Get ‘Em on Task requires a computer or application to provide a random auditory signal in the classroom to alert teachers and students to monitor behaviors and participation. When the sound goes off, the teacher identifies students by name who are off-task, and instructs them to mark an X on their individual score cards; students who are on-task are praised and told to give themselves a point. At the end of a designated time period, students use the points for a reward, pre-determined by the students and teacher.

How to:

Materials:

- Get ‘Em on Task computer program, OR App for automatic auditory signal

- Point Card for each student

- Classroom bank to record points

- Reward menu with cost (in points) for reward items

- As a class, identify desired behaviors (within varied learning situations: whole group, small group, peer work, or individual work). Model, demonstrate, and role play to ensure student understanding. Use Rules Within Routines Matrix may be effective and may help with generalization to other classes and settings.

- Explain that students will have the opportunity to earn rewards for appropriate behavior.

- As a class, identify desired rewards (ex: special activities, snacks). Designate the point value/cost for the various items. Create goals based on points per day (for example, 10 points available per day). Pre-determine when students can use their banked points to exchange for a reward item. For example, depending on the age and ability of students, and in order to build their endurance for demonstrating the appropriate behaviors, you may want to offer the reward exchange opportunity in smaller increments, and gradually extend this time (end of a class period, middle of the day, end of the day, end of the week.)

- As a class, identify behaviors to avoid, particularly in areas where students have struggled (i.e. negative language, not cooperating during group work).

- Give each student a Point Card. (Create individual point cards here.)

- When the computer signal sounds, scan the classroom:

- Identify students who are off task by name. They receive no points and students/staff (depending on age) mark an X on the Point Card. Be clear that students are being called out not as a punishment but to note that they need to regulate themselves. This intervention brings attention to the undesired behaviors first; to provide a more positive intervention, quickly note the names of students who are on-task.

- Praise students who are on task and tell them to award themselves a point. Be very specific as to the behaviors they were exhibiting.

- At the end of the day, students calculate their points and add them to their bank total.

- Review progress with students, pointing out specific behaviors that earned credit and raised their bank score. Acknowledge improvement publicly as appropriate for each student.

- For students who earned few to no points, discuss the desired behaviors and goals for behavior and points earned for the next class.

Reference:

Kraemer, E. E., Davies, S. C., Arndt, K. J., & Hunley, S. (2012). A comparison of the Mystery Motivator and the Get ‘Em On Task interventions for off-task

behaviors. Psychology in the Schools, 49(2), 163-175.

Resources:

Mystery Motivator (Tier II)

A chart is created to identify and track daily behaviors. If appropriate behaviors are demonstrated, the corresponding space on the chart is selected, which may show a Mystery Motivator symbol, whereby a prize is selected from a menu of options.

The Mystery Motivator can be used class wide or with individual.. Desired and expected behaviors are clearly defined and described. A chart is created to identify and track daily behaviors. If appropriate behaviors are demonstrated, the corresponding space on the chart is selected, which may show a Mystery Motivator symbol, whereby a prize is selected from a menu of options. The unknown nature of the reward serves to build and hold student interest.

How to:

Materials:

Tips:

Kraemer, E. E., Davies, S. C., Arndt, K. J., & Hunley, S. (2012). A comparison of the Mystery Motivator and the Get ‘Em On Task interventions for off-task

behaviors. Psychology in the Schools, 49(2), 163-175.

Resources:

- Student Point Card

- Ideas that Work (Points Sheets/Behavior Report Cards)

Mystery Motivator (Tier II)

A chart is created to identify and track daily behaviors. If appropriate behaviors are demonstrated, the corresponding space on the chart is selected, which may show a Mystery Motivator symbol, whereby a prize is selected from a menu of options.

The Mystery Motivator can be used class wide or with individual.. Desired and expected behaviors are clearly defined and described. A chart is created to identify and track daily behaviors. If appropriate behaviors are demonstrated, the corresponding space on the chart is selected, which may show a Mystery Motivator symbol, whereby a prize is selected from a menu of options. The unknown nature of the reward serves to build and hold student interest.

How to:

Materials:

- “Invisible” markers (ex. Crayola Color Switchers: watercolor markers that include a pen with transparent ink

- Weekly behavior charts (place an “invisible” mark—star, “MM”—on a space. When students demonstrate appropriate behaviors, a space on the chart is colored in. When the marker writes over the “invisible” ink, the mark appears and students receive the reward).

- Reward menu (ex. Extra recess, 5 min. for a class game, snacks, gum, extra reading time

- Reward items

- As a class, identify desired behaviors (within varied learning situations: whole group, small group, peer work, or individual work). Model, demonstrate, and role play to ensure student understanding. Use of Rules Within Routines Matrix may be effective and may help with generalization to other classes and settings. (link to that.)

- Explain that students will have the opportunity to earn rewards for appropriate behavior.

- As a class, identify desired rewards (ex: special activities, snacks). Designate the point value/cost for the various items. Create goals based on points per day (for example, 10 points available per day). Pre-determine when students can use their banked points to exchange for a reward item. For example, depending on the age and ability of students, and in order to build their endurance for demonstrating the appropriate behaviors, you may want to offer the reward exchange opportunity in smaller increments, and gradually extend this time (end of a class period, middle of the day, end of the day, end of the week.)

- As a class, identify behaviors to avoid, particularly in areas where students have struggled (i.e. negative language, not cooperating during group work).

- Identify the minimum behavioral requirements for earning the reward.

- When the class demonstrates identified on-task behaviors, a space on the chart is colored in. (If the Mystery Mark appears, the class earns the reward. If the Mystery Mark does not appear, verbally praise the students for their behavior and efforts.

- If the class earns all the possible Mystery Motivators for the week, they earn the

reward from a Bonus Points menu.

Tips:

- Vary where the Mystery Mark is located so there is not a pattern for students to follow.

- This system can be modified for use with various age ranges.

- Start small: perhaps use this system with only one class period/subject a day, or just in the mornings or afternoons. As students build up endurance for demonstrating the appropriate behaviors, use the intervention across more of the school day.

Reference:

Kraemer, E. E., Davies, S. C., Arndt, K. J., & Hunley, S. (2012). A comparison of the Mystery Motivator and the Get ‘Em On Task interventions for off-task

behaviors. Psychology in the Schools, 49(2), 163-175.

Resources:

Kraemer, E. E., Davies, S. C., Arndt, K. J., & Hunley, S. (2012). A comparison of the Mystery Motivator and the Get ‘Em On Task interventions for off-task

behaviors. Psychology in the Schools, 49(2), 163-175.

Resources:

aggressive behaviors

When Off-Task Behaviors escalate to forms of verbal and physical aggression further intervention is needed.

Verbal aggression includes comments in spoken, written, or drawn format (such as mean-spirited teasing, criticism, and threats) intended to hurt another individual by making them uncomfortable, embarrassed, afraid, or intimidated.

Verbal aggression may be an ignored and under-reported problem. Because the shame associated with being victimized is strong, many students will refuse to discuss or report it, even to their families. Other students who witness an incident may not speak out of fear of becoming targets themselves.

Physical aggression is behavior causing physical harm towards others. Examples include hitting, kicking, biting, using weapons, pinching, scratching, spitting, throwing objects and property destruction.

Instead of sending students out of the classroom, the following Tier 2 interventions are designed to empower teachers and students by providing instruction and support. The goal is to maintain a community of learning for all by increasing on-task (appropriate behaviors) and decreasing off-task behaviors.

Here are some Tier 2 research based strategies that can be used with an individual to increase appropriate behaviors:

Check in/Check Out – The student will begin and end the day with positive interactions. In addition, the student will be reminded to demonstrate appropriate behaviors across all settings. Students have a daily Check In every morning (with a specific person, at a specific place and time), earn points throughout the day for exhibiting appropriate behaviors, and have an afternoon Check Out to monitor their efforts towards meeting their daily goal. Parents are sent copies of this form as well.

Verbal aggression may be an ignored and under-reported problem. Because the shame associated with being victimized is strong, many students will refuse to discuss or report it, even to their families. Other students who witness an incident may not speak out of fear of becoming targets themselves.

Physical aggression is behavior causing physical harm towards others. Examples include hitting, kicking, biting, using weapons, pinching, scratching, spitting, throwing objects and property destruction.

Instead of sending students out of the classroom, the following Tier 2 interventions are designed to empower teachers and students by providing instruction and support. The goal is to maintain a community of learning for all by increasing on-task (appropriate behaviors) and decreasing off-task behaviors.

Here are some Tier 2 research based strategies that can be used with an individual to increase appropriate behaviors:

Check in/Check Out – The student will begin and end the day with positive interactions. In addition, the student will be reminded to demonstrate appropriate behaviors across all settings. Students have a daily Check In every morning (with a specific person, at a specific place and time), earn points throughout the day for exhibiting appropriate behaviors, and have an afternoon Check Out to monitor their efforts towards meeting their daily goal. Parents are sent copies of this form as well.

Check in/Check Up/Check Out - Similar to the Check In/Check Out, this is designed for students who need more support and attention in the day. In addition to the morning and afternoon check in, students meet with their mentor adult for a mid-day Check Up. During this mid-day meeting, the student and mentor review the points earned thus far (aiming for 50%), acknowledge appropriate behaviors and decisions, earn rewards and receive verbal praise, and discuss areas of difficulty.

Self-Determination/Self-Monitoring - This strategy teaches students how to identify the behaviors they want to exhibit and provides a means of tracking their progress towards that goal.

Self-Determination/Self-Monitoring - This strategy teaches students how to identify the behaviors they want to exhibit and provides a means of tracking their progress towards that goal.

teacher-focused interventions

Just as teachers are responsible for teaching reading and math, teachers also need to teach appropriate behaviors. And just as we do not expect to have one session with a struggling reader before we see success, we need to be aware that behavioral changes will also take time.

The following interventions require time to which takes away from instructional time. This may feel like a waste of time. However, the opposite is true: when time is spent teaching students appropriate behaviors, this actually increases the amount of time the entire class is engaged in instruction.

If time is not spent teaching students appropriate behaviors, the problematic behaviors continue. Students are often removed from class, missing instruction and falling behind academically.

Here are Tier 2 research based Teacher-Focused interventions for teaching appropriate behaviors:

Pre-correction/Prompting Appropriate Behavior

Pre-correction is a research based practice that increases appropriate and on-task behaviors and decreases unwanted behaviors.

A teacher explicitly states the desired behavior(s) before a task. This simple strategy is effective across ages, school settings, and ability levels. The art of pre-correction is to anticipate the behaviors that may occur and review the expectations of the task in a clear and positive way, prior to engagement.

Implementation:

If time is not spent teaching students appropriate behaviors, the problematic behaviors continue. Students are often removed from class, missing instruction and falling behind academically.

Here are Tier 2 research based Teacher-Focused interventions for teaching appropriate behaviors:

Pre-correction/Prompting Appropriate Behavior

Pre-correction is a research based practice that increases appropriate and on-task behaviors and decreases unwanted behaviors.

A teacher explicitly states the desired behavior(s) before a task. This simple strategy is effective across ages, school settings, and ability levels. The art of pre-correction is to anticipate the behaviors that may occur and review the expectations of the task in a clear and positive way, prior to engagement.

Implementation:

- Provide verbal cue/reminder, stated in the positive (Walk calmly down the hall vs. Don’t run!)

- Link verbal cues to school wide/class expectations/rules (Be safe by walking to lunch)

- Model the behavior (Who can show the way we walk to lunch?)

- Verbal, visual/gestural (sign language), physical (Slow down hand signal.)

- Specific and frequent

- Directly prior to (minutes before) behavior is expected (Right before the lunch bell rings this behavior is reviewed.)

- Actively supervise (“move around, visually scan, and interact with students” Faul, 2012)

- Reinforce appropriate/expected behavior with verbal/gestural recognition (a thumbs up, a high five) praise

- Write prompts to help yourself remember and deliver explicit statements to individual students, based on their behavioral expectations and goals.

References:

Colvin, J. O., Sugai, G., Good, R., & Lee, Y. (1997). Using active supervision and pre-correction to improve transition behaviors in an elementary school. School Psychology Quarterly, 21, pp. 262-285.

Faul, A., Stepensky, K., & Simonsen, B. (2012). The effects of prompting appropriate behavior on the off-task behavior of two middle school students. Journal of Positive behavior Interventions, 14(47), pp. 47-55. doi: 10.1177/1098300711410702.

Colvin, J. O., Sugai, G., Good, R., & Lee, Y. (1997). Using active supervision and pre-correction to improve transition behaviors in an elementary school. School Psychology Quarterly, 21, pp. 262-285.

Faul, A., Stepensky, K., & Simonsen, B. (2012). The effects of prompting appropriate behavior on the off-task behavior of two middle school students. Journal of Positive behavior Interventions, 14(47), pp. 47-55. doi: 10.1177/1098300711410702.

Teacher Attention Delivered on Fixed-Time Schedule

This strategy has been found to increase on-task behaviors and decrease off-task behaviors. This intervention is most effective for students who are misbehaving to get attention. The effectiveness of this strategy may be due to the praise students receive for on-task behaviors and the assistance they receive through redirection to engage in appropriate behaviors.

How To:

Austin, J. L., & Soeda, J. M. (2008). Fixed-time teacher attention to decrease off-task behaviors of typically developing third graders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41, 279-283. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-279

Riley, J. L., McKevitt, B., C., Shriver, M. D., & Allen, K. D. (2011). Increasing on-task behavior using teacher attention delivered on a fixed-time schedule. Journal of Behavioral Education, 20, 149-162. doi: 10.1007/s10864-011-9132-y

Simonsen, B., Little, C. A., & Fairbanks, S. (2010). Effects of task difficulty and teacher attention on the off-task behavior of high-ability students with behavior issues. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 32(2), 245-260.

This strategy has been found to increase on-task behaviors and decrease off-task behaviors. This intervention is most effective for students who are misbehaving to get attention. The effectiveness of this strategy may be due to the praise students receive for on-task behaviors and the assistance they receive through redirection to engage in appropriate behaviors.

How To:

- Set alarm to vibrate/signal at chosen designated time (every 4-5 minutes, depending on the severity or obtrusiveness of the behavior).

- Upon receiving the signal, provide individual students with specific feedback

- praise for on-task behavior (“I notice you’re generating a list of questions from the reading to share later; nicely done!”)

- redirection for appropriate behavior (not commenting on the problematic behavior (“Have you completed the reading? Begin writing a list of questions so you can share with the class soon. We want to hear your thoughts.” Instead of “You’re not working on the assignment again.”)

- Interact with the student as usual in between the signals, but try to include more comments with specific feedback and encouragement instead of negative comments

- Cell phone for alert via sound or vibration

Austin, J. L., & Soeda, J. M. (2008). Fixed-time teacher attention to decrease off-task behaviors of typically developing third graders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41, 279-283. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-279

Riley, J. L., McKevitt, B., C., Shriver, M. D., & Allen, K. D. (2011). Increasing on-task behavior using teacher attention delivered on a fixed-time schedule. Journal of Behavioral Education, 20, 149-162. doi: 10.1007/s10864-011-9132-y

Simonsen, B., Little, C. A., & Fairbanks, S. (2010). Effects of task difficulty and teacher attention on the off-task behavior of high-ability students with behavior issues. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 32(2), 245-260.

REPETITIVE/STEREOTYPIC/SELF-STIMULATORY BEHAVIORS

Repetitive behaviors can either be vocal or motoric.

The following are common vocal repetitive behaviors exhibited by students:

Repetitive motor behaviors may include:

These behaviors seem to lack a social function or motivation.

However, these behaviors may in fact be meeting a need for the student by:

There is evidence to support that reducing repetitive behavior in students can increase engagement and communication skills of the student.

Here are some Tier 2 research based strategies that can be used with an individual to increase appropriate behaviors:

Self-Monitoring with Rewards - This strategy can be used with students who engage in repetitive verbal behavior, that seems to serve no communication function. The student is taught to identify “quiet” vs “noisy” behavior. Student is given a “quiet” visual reminder, and records whether or not he/she has been quiet during the time interval. Student receives rewards for reaching a goal percentage of quiet intervals.

Response Interruption and Redirection (RIRD)

This strategy can be used for either vocal or motor repetitive behavior. When the student engages in the repetitive behavior, the teacher gains his/her attention by calling out the student’s name in a neutral tone.

If the behavior is vocal, the teacher then follows up with a series of questions in an attempt to elicit a response that may be aligned with individual interests (“How old are you?” “What is your favorite season?”).

If the behavior is motor, the teacher may request a verbal or motor response (“Touch your nose.” “Stand up.”).

Toy/Book Conditioning

This intervention may be appropriate for students who spend their free time engaging in stereotypic behaviors and disengaged from toys and books.

- humming

- nonsense words

- repeating sounds or phrases

- echolalia

Repetitive motor behaviors may include:

- flapping of hands

- finger flexing

- rocking of body

These behaviors seem to lack a social function or motivation.

However, these behaviors may in fact be meeting a need for the student by:

- providing sensory regulation

- increasing wait time for processing

- attempting communication

There is evidence to support that reducing repetitive behavior in students can increase engagement and communication skills of the student.

Here are some Tier 2 research based strategies that can be used with an individual to increase appropriate behaviors:

Self-Monitoring with Rewards - This strategy can be used with students who engage in repetitive verbal behavior, that seems to serve no communication function. The student is taught to identify “quiet” vs “noisy” behavior. Student is given a “quiet” visual reminder, and records whether or not he/she has been quiet during the time interval. Student receives rewards for reaching a goal percentage of quiet intervals.

Response Interruption and Redirection (RIRD)

This strategy can be used for either vocal or motor repetitive behavior. When the student engages in the repetitive behavior, the teacher gains his/her attention by calling out the student’s name in a neutral tone.

If the behavior is vocal, the teacher then follows up with a series of questions in an attempt to elicit a response that may be aligned with individual interests (“How old are you?” “What is your favorite season?”).

If the behavior is motor, the teacher may request a verbal or motor response (“Touch your nose.” “Stand up.”).

Toy/Book Conditioning

This intervention may be appropriate for students who spend their free time engaging in stereotypic behaviors and disengaged from toys and books.

Students are taught to interact with toys and books through a structured activity which includes rewards. This has been shown to lead to more book interaction and toy play during free time, and less repetitive and passive behaviors.

References for off-task behaviors

Allensworth, E. M. & Easton, J. Q. (2007). What matters for staying on-track and graduating in Chicago public high schools:

A close look at course grades, failures, and attendance in the freshman year. Retrieved from Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago website: https://consortium.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/publications/07%20What%20Matters%20Final.pdf.

Hintze, J. M., Volpe, R. J., & Shapiro, E. S. (2002). Best practices in the systematic direct observation of student behavior. Best practices in school psychology, 4, 993-1006.

Kraemer, E. E., Davies, S. C., Arndt, K. J., & Hunley, S. (2012). A comparison of the Mystery Motivator and the Get ‘Em On Task interventions for off-task behaviors. Psychology in the Schools, 49(2), 163-175. doi: 10.1002/pits.20627

Shapiro, E.S. (2004). Academic skills problems: Direct assessment and intervention. New York: Guilford.

Swoszowski, N. C., McDaniel, S. C., Jolivette, K., Melius, P. (2013). The effects of tier II check-in/check-out including adaptation for non-responders on the off-task behavior of elementary students in a residential setting. Education and Treatment of Children, 36(3), 63-79.

A close look at course grades, failures, and attendance in the freshman year. Retrieved from Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago website: https://consortium.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/publications/07%20What%20Matters%20Final.pdf.

Hintze, J. M., Volpe, R. J., & Shapiro, E. S. (2002). Best practices in the systematic direct observation of student behavior. Best practices in school psychology, 4, 993-1006.

Kraemer, E. E., Davies, S. C., Arndt, K. J., & Hunley, S. (2012). A comparison of the Mystery Motivator and the Get ‘Em On Task interventions for off-task behaviors. Psychology in the Schools, 49(2), 163-175. doi: 10.1002/pits.20627

Shapiro, E.S. (2004). Academic skills problems: Direct assessment and intervention. New York: Guilford.

Swoszowski, N. C., McDaniel, S. C., Jolivette, K., Melius, P. (2013). The effects of tier II check-in/check-out including adaptation for non-responders on the off-task behavior of elementary students in a residential setting. Education and Treatment of Children, 36(3), 63-79.

references for repetitive behaviors

Ahrens, E. N., Lerman, D. C., Kodak, T., Worsdell, A. S., & Keegan, C. (2011). Further evaluation of response interruption and redirection as treatment for stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,44(1), 95–108. http://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2011.44-95

Colón, C. L., Ahearn, W. H., Clark, K. M., & Masalsky, J. (2012). The effects of verbal operant training and response interruption and redirection on appropriate and inappropriate vocalizations.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(1), 107–120. http://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2012.45-107

Liu-Gitz, L., & Banda, D. R. (2009). A replication of the RIRD strategy to decrease vocal stereotypy in a student with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 25 (December 2009), 77–87.http://doi.org/10.1002/bin

Saini, V., Gregory, M. K., Uran, K. J., & Fantetti, M. a. (2015). Parametric analysis of response interruption and redirection as treatment for stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,48(1), 96–106. http://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.186

Colón, C. L., Ahearn, W. H., Clark, K. M., & Masalsky, J. (2012). The effects of verbal operant training and response interruption and redirection on appropriate and inappropriate vocalizations.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(1), 107–120. http://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2012.45-107

Liu-Gitz, L., & Banda, D. R. (2009). A replication of the RIRD strategy to decrease vocal stereotypy in a student with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 25 (December 2009), 77–87.http://doi.org/10.1002/bin

Saini, V., Gregory, M. K., Uran, K. J., & Fantetti, M. a. (2015). Parametric analysis of response interruption and redirection as treatment for stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,48(1), 96–106. http://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.186

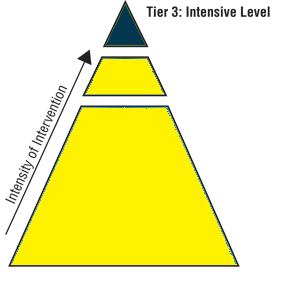

TIER 3: INTENSIVE

ELOPEMENT/RUNNING AWAY

Elopement is often referred to as running away, bolting, wandering, AWOL, or being out of bounds. Elopement or running away is a serious due to the dangers that may occur for students without direct adult supervision

Elopement is defined as leaving the designated area without permission. It can be based upon:

There are 2 common reasons a student may elope:

If the student is eloping to get something or somewhere preferred, it may be that the student does not have the social communications skills necessary to get permission or notify someone.

If the student is eloping to escape something or somewhere non-preferred, it is likely the student does not have the social communication skills necessary to voice their needs.

Once you’ve determine why the individual is eloping, here are Tier 3 strategies which may be helpful.

- a specific boundary (leaving the classroom)

- a specific measurement (3-6 feet away)

There are 2 common reasons a student may elope:

- To get something or somewhere preferred

- To escape something or somewhere non-preferred.

If the student is eloping to get something or somewhere preferred, it may be that the student does not have the social communications skills necessary to get permission or notify someone.

If the student is eloping to escape something or somewhere non-preferred, it is likely the student does not have the social communication skills necessary to voice their needs.

Once you’ve determine why the individual is eloping, here are Tier 3 strategies which may be helpful.

FUNCTION OF THE BEHAVIOR: ESCAPE

Building Incremental Success: Graduated Exposure and Contingent Rewards

This intervention for handling running away/elopement is useful for students who have an aversion to a specific place or activity (ie. PE class, assembly), and therefore elope from those environments or actively resist entering certain locations. Students may become agitated or frightened merely by approaching these locations, and the repeated exposure leads to a de-sensitivity to the specific settings. The first goal is to get the student to enter the setting, and eventually to participate in the activity within that learning environment. To slowly support them in reaching specific distance goals along the way (ie. half way to PE class, ¾ of the way), and rewarding them for doing so with a reinforcer (sticker, gum) and verbal praise. The distance is gradually increased (based on success), until the student is able to enter the environment. The goal then moves to participating and completing the expected tasks within the learning environment. This intervention requires additional staffing to support implementation.

*Use the resource tracker below to help guide you in following these steps.

How To:

First, understand the behavior (Phase 1: Baseline):

First, measure how close the student will come to the setting without displaying negative behaviors (bolting, aggression).

Next, work to get the student safely to the setting:

Then, work to get the student to enter the setting:

Finally, work to get the student to participate:

This intervention for handling running away/elopement is useful for students who have an aversion to a specific place or activity (ie. PE class, assembly), and therefore elope from those environments or actively resist entering certain locations. Students may become agitated or frightened merely by approaching these locations, and the repeated exposure leads to a de-sensitivity to the specific settings. The first goal is to get the student to enter the setting, and eventually to participate in the activity within that learning environment. To slowly support them in reaching specific distance goals along the way (ie. half way to PE class, ¾ of the way), and rewarding them for doing so with a reinforcer (sticker, gum) and verbal praise. The distance is gradually increased (based on success), until the student is able to enter the environment. The goal then moves to participating and completing the expected tasks within the learning environment. This intervention requires additional staffing to support implementation.

*Use the resource tracker below to help guide you in following these steps.

How To:

First, understand the behavior (Phase 1: Baseline):

First, measure how close the student will come to the setting without displaying negative behaviors (bolting, aggression).

- Tell the student, “_____, it is time to go to the _____ (setting).” Walk with the student, until he/she displays behavior.

- Place a marker on the floor, to later measure the closest distance the student will tolerate.

- Tell the student, “It is time to go back to the classroom.”

- To calculate a meaningful baseline, get an average for the setting across multiple attempts (at least 3).

- Possible rewards include small edibles (raisin, goldfish), or another small reward such as a sticker.

- Pair the reward with specific verbal praise, “Nice job walking safely.”

Next, work to get the student safely to the setting:

- A second staff person stands on the distance marker that sets the goal for the student.

- If the student reaches the marker, they receive their small reward, paired with verbal praise, and return to the classroom.

- If problem behaviors occur, no reward is given and the student is prompted to return to the classroom.

- When the student is successful at the distance two instances in a row, increase the distance 20%.

- Continue with these steps until the student is able to arrive at the setting, for three consecutive sessions.

Then, work to get the student to enter the setting:

- After three consecutive successes of reaching the doorway of the setting, the second staff person is now there to greet the student, and reward them for stepping into the environment.

- A timer is set once the student enters the setting, to cue the student how long they will remain in the setting. Once the timer goes off, the student is rewarded and then returns to class. If the student engages in negative behavior prior to the timer going off, the time and behaviors are recorded, and the student is prompted to return to class.

- The expectation for time spent in the setting is adjusted as needed, and may be set at as low as 2 seconds initially, and slowly built up with successes.

- As the student becomes more successful, the rewards will be faded out.

Finally, work to get the student to participate:

- Once the student is able to enter the setting, and remain in the setting for a meaningful amount of time, rewards are then switched to match participation goals.

- Student can be rewarded for a specific action (running one lap), or for being a part of the group for a specific amount of time (sitting in circle time for 3 minutes).

- As the student becomes more successful, rewards can shift to tokens, which can later be translated into larger rewards

Reference:

Schmidt, J. D., Luiselli, J. K., Rue, H., & Whalley, K. (2013). Graduated exposure and positive reinforcement to overcome setting and activity avoidance in an

adolescent with autism. Behavior Modification, 37(1), 128-142. doi: 10.1177/0145445512456547

Resources:

Schmidt, J. D., Luiselli, J. K., Rue, H., & Whalley, K. (2013). Graduated exposure and positive reinforcement to overcome setting and activity avoidance in an

adolescent with autism. Behavior Modification, 37(1), 128-142. doi: 10.1177/0145445512456547

Resources:

FUNCTION OF THE BEHAVIOR: ESCAPE/AVOID OR GAIN ATTENTION

Functional Communication Training (FCT)

Functional Communication Training (FCT) is a well researched strategy that teaches students specific communication skills in order to meet their needs; essentially the elopement behavior is being replaced with positive communication skills. The student can make their request verbally (requesting an item or break) or non-verbally (pointing to the desired item or activity, using a cue card or a previously agreed upon sign or symbol, or using a Picture Exchange Communication System [PECS]).

Essentially the elopement behavior is being replaced using positive communication skills to gain what the student wants.

How To:

Functional Communication Training (FCT) is a well researched strategy that teaches students specific communication skills in order to meet their needs; essentially the elopement behavior is being replaced with positive communication skills. The student can make their request verbally (requesting an item or break) or non-verbally (pointing to the desired item or activity, using a cue card or a previously agreed upon sign or symbol, or using a Picture Exchange Communication System [PECS]).

Essentially the elopement behavior is being replaced using positive communication skills to gain what the student wants.

How To:

- First, understand the level of communication:

- The child’s communication level must be understood. In order for FCT to work, the communication training must be centered on their level of functioning.

- Verbal training can vary from simple one word statements (“break”), to more complex sentences (“I need a break on my beanbag”).

- Some students with limited language may require non-verbal strategies such as PECS. Regardless of the student’s communication level, when students are stressed their communication abilities may be limited. Therefore, it may be meaningful to have nonverbal choices (cue card, symbols or sign language).

- In order to respect the student’s need for privacy, a previously agreed upon phrase, sign, or symbol can be established, while still providing them a more positive means to communicate.

Then, identify the reason for the behavior (function):

Intervention:

- Use the ABC chart to collect data regarding the antecedents that occur prior to the elopement. This information will help to create the phrases that the student can be taught to use to get what they need, instead of running away.

- Establish why the student is running away (function of the behavior): was the child attempting to gain something, such as access to a toy or access to adult attention? Or was the child trying to avoid something, such as classwork, or interaction with peers? Based on the function, the focus of the FCT training will vary.

- Once the function of the behavior is established, specific communication is taught using sentence frames or phrases, so the student is able to ask for what he/she needs, instead of running away.

- Data should be collected regarding the student’s maximum ability to engage in a specific task or subject matter. For example, how long can he/she engage in the math lesson before eloping from the task? Or, how many minutes of assembly can the student attend before eloping? The focus of the data collection should be on the content areas with which the student struggles.

Intervention:

- It is important to teach students the functional communication skills before they begin to engage in the undesirable behavior. This can be practiced during calm/successful times of day.

- Prompt students to use their verbal phrases or may be given the choice to use symbols, sign language, or PECs.

- Students should be prompted to use their words prior to reaching their “maximum.” For example, if a student can participate in a writing task for only 10 minutes before running away, prompt them at 8 minutes to ask for a break.

- More prompts are needed initially, such as “Do you need a break?” and later as the student is able to use their phrases more consistently the prompts can be less specific, “What do you need right now?”

- If the student successfully requests the break prior to eloping, the student is given immediate access to fulfill the request.

- As the child is more successful, the tasks become longer and the prompts are faded. The child may be prompted more generally, “What do you want?”

References:

Carr, E. G., & Durand, M. (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18(2),

111-126. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111

Piazza, C.C., Hanley, G.P., Bowman, L.G., Ruyter, J.M., Lindauer, S.E., & Saiontz, D.M. (1997). Functional analysis and treatment of elopement. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 30(4), 653-672. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-653

Tarbox, R.S.F., Wallace, M.D., & Williams, L. (2003). Assessment and treatment of elopement: A replication and extension. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 36(2), 239-244. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-239

Wacker, P.W., Lee, J.F., Padilla Dalamau, Y.C., Kopelman, T.G., Lindgren, S.D., Kuhle, J., . . . Waldron, D.B. (2013). Conducting functional communication

training via Telehealth to reduce the problem behavior of young children with autism. Journal of Developmental and PhysicalDisabilities, 25, 35-48.

doi: 10.1007/s10882-012-9314-0

Resources:

Carr, E. G., & Durand, M. (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18(2),

111-126. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111

Piazza, C.C., Hanley, G.P., Bowman, L.G., Ruyter, J.M., Lindauer, S.E., & Saiontz, D.M. (1997). Functional analysis and treatment of elopement. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 30(4), 653-672. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-653

Tarbox, R.S.F., Wallace, M.D., & Williams, L. (2003). Assessment and treatment of elopement: A replication and extension. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 36(2), 239-244. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-239

Wacker, P.W., Lee, J.F., Padilla Dalamau, Y.C., Kopelman, T.G., Lindgren, S.D., Kuhle, J., . . . Waldron, D.B. (2013). Conducting functional communication

training via Telehealth to reduce the problem behavior of young children with autism. Journal of Developmental and PhysicalDisabilities, 25, 35-48.

doi: 10.1007/s10882-012-9314-0

Resources:

FUNCTION OF THE BEHAVIOR: GAIN ATTENTION

Positive Attention: Non-Contingent Attention

This intervention is implemented for students who run away to get attention (being chased or the desire for one on one time with an adult). Instead, consistent, positive attention is given to the student while they are “in bounds” or in the expected area.

This intervention is implemented for students who run away to get attention (being chased or the desire for one on one time with an adult). Instead, consistent, positive attention is given to the student while they are “in bounds” or in the expected area.

How To:

Collect data regarding what triggers the behavior, and how the student is rewarded for the elopement. For example, does the student gain attention from peers? Does the student run away when he/she is left alone without adult support? Does the student show success with additional staffing support?

Implementation:

Collect data regarding what triggers the behavior, and how the student is rewarded for the elopement. For example, does the student gain attention from peers? Does the student run away when he/she is left alone without adult support? Does the student show success with additional staffing support?

Implementation:

- Non-contingent attention may vary depending on the student, depending on what type of attention they most desire. Attention is given to the student on a consistent schedule that may vary with age and need, beginning as often as every 30 seconds.

- Types of attention: specific verbal praise (“Thank you for being in your seat”), eye contact, high fives, or keeping close proximity with the student.

- When the student does engage in elopement, the behavior is responded to with the least amount of attention possible.

- Example: Face away from the student, minimize verbal engagement, and guide them towards the appropriate location, where they are given a time out (away from adult and student attention) in a safe place.

- The student can also benefit from Functional Communication Training (FCT), with a focus on prompts to gain attention, and should be practicing FCT skills as well, to decrease the behavior.

Reference:

Kodak, T., Grow, L., & Northup, J. (2004). Functional analysis and treatment of elopement for a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 37(2), 229-232.

Resources:

Kodak, T., Grow, L., & Northup, J. (2004). Functional analysis and treatment of elopement for a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 37(2), 229-232.

Resources:

- Collecting data: Antecedent/Behavior/Consequence (ABC)

- The Iris Center

|

|

Marin County SELPA commissioned Dominican University of California’s Department of Special Education to identify evidence-based behavioral practices to support students, teachers, and local schools. In particular, the task was to identify positive, evidence-based classroom practices leading to academic and behavioral success.

Dominican University of California is located in Marin County and offers graduate programs that culminate in a Master of Science (MS) in Education degree. These programs are designed for educators and other professionals who are interested in teaching and seek preparation for leadership roles and responsibilities

|